Guest Blog by Katelynn Northam

I remember distinctly the moment when I realized how broken our voting system is. It was the night of the 2011 election and I was unwaveringly optimistic – in a way that only a fourth-year political science student can be – about the virtues of democratic participation.

Imagine my surprise when the Conservatives not only won again, but won a majority government with only 39% of the popular vote. How, I thought, can any party claim the right to unilaterally introduce policies when they don’t even have a mandate from half of the voting public?

That was the moment when I realized that our first-past-the-post (FPTP) voting system had to go, and now it seems that many others across this country agree. So what exactly is the problem with FPTP that we’re solving for?

One of its biggest flaws, as we saw in 2011, is that FPTP leaves the power to decide who wins elections to a few key ‘battleground ridings’ or ‘swing ridings’. There are many ‘safe ridings’ across Canada that are fairly likely to go one way, so parties tend to focus on the narrower, less predictable races, called ‘swing ridings’. This means that the votes of voters in swing ridings are disproportionately powerful, and that parties are more likely to focus on them when developing their platforms.

The problem is that FPTP also makes it difficult for voters within ‘swing ridings’ to express their preferences accurately. A multi-party system where the right-wing is consolidated in one party and the centre-left is split among several, will inevitably lead to ‘vote splitting’. It is possible (and common) for a candidate to win a seat with less than 50% sometimes less than 40% of the vote, and therefore for a single party to win a plurality or even a majority of seats with a much lower percentage of the popular vote.

Defenders of FPTP often say it allows for ‘decisive defeats’ of unpopular governments – but it is not always so easy for people to kick out unpopular governments because of this vote-splitting.

For example, Harper never had broad support from a majority of Canadians. About two-thirds of the country were unhappy with his performance in 2011, so they did what they should do – they voted for someone else.

Then the anti-Harper vote split among the three major opposition parties within those key battleground ridings, allowing the Conservatives to win a number of seats with less than 50% of the popular vote. And voila – we had a four-year majority government.

So what recourse do voters have in an FPTP system when they want to vote out a government? Because voters only get one vote, they have to make a choice – vote for who they like, or vote for the person most likely to defeat the person they dislike the most. Sometimes these are the same candidates, but for many voters, they are not. This is known as ‘strategic voting’.

As the Better Choices report rightly points out, the so-called decisive victories and defeats that FPTP brings about often come down to a few thousand people who happen to live in the right place. In 2008 Harper got 37% of the popular vote and won 143 seats. In 2011 he got 39% of the vote and 166 seats. That’s a big jump in seats compared to a relatively small jump in popular vote. Ah, math.

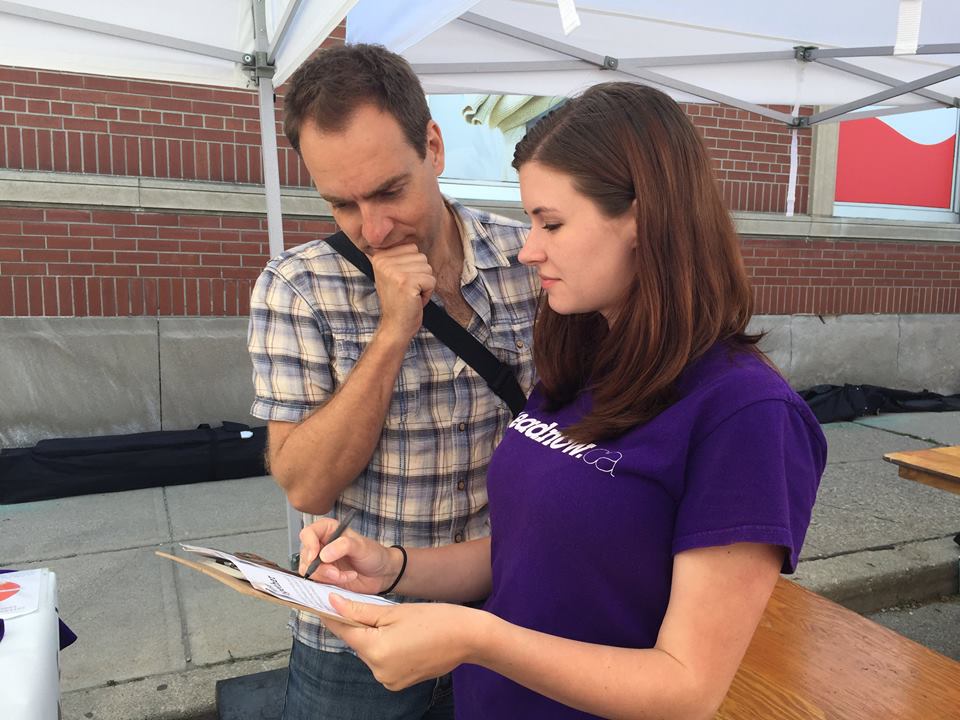

These inherent flaws in FPTP are why many people, including Leadnow, the organization that I work with, turned to strategic voting in 2015 to hold the Harper government accountable in the last election. It felt like the best way to actually express the true will of the people.

But we shouldn’t have to do it ever again. Which is why we have launched the Vote Better campaign to get proportional representation at the federal level. Our members, and I believe most Canadians, don’t want to cast ballots out of fear of unintended consequences. They want to reward the parties that best capture their values, and they want 39% of the vote to mean 39% of the power.

Solve for that, and we’re on our way to having a fairer and more mature democracy.

—

Katelynn Northam is an organizer with the national group, Leadnow. She’s a graduate of the Masters of Political Science program at Dalhousie University, and self-identifying democrageek.

The views expressed in guest blog posts are those of the contributors and not necessarily those of the Springtide Collective. We invite a diversity of commentary and opinions encourage those who wish to express theirs on the Springtide blog to get in touch.