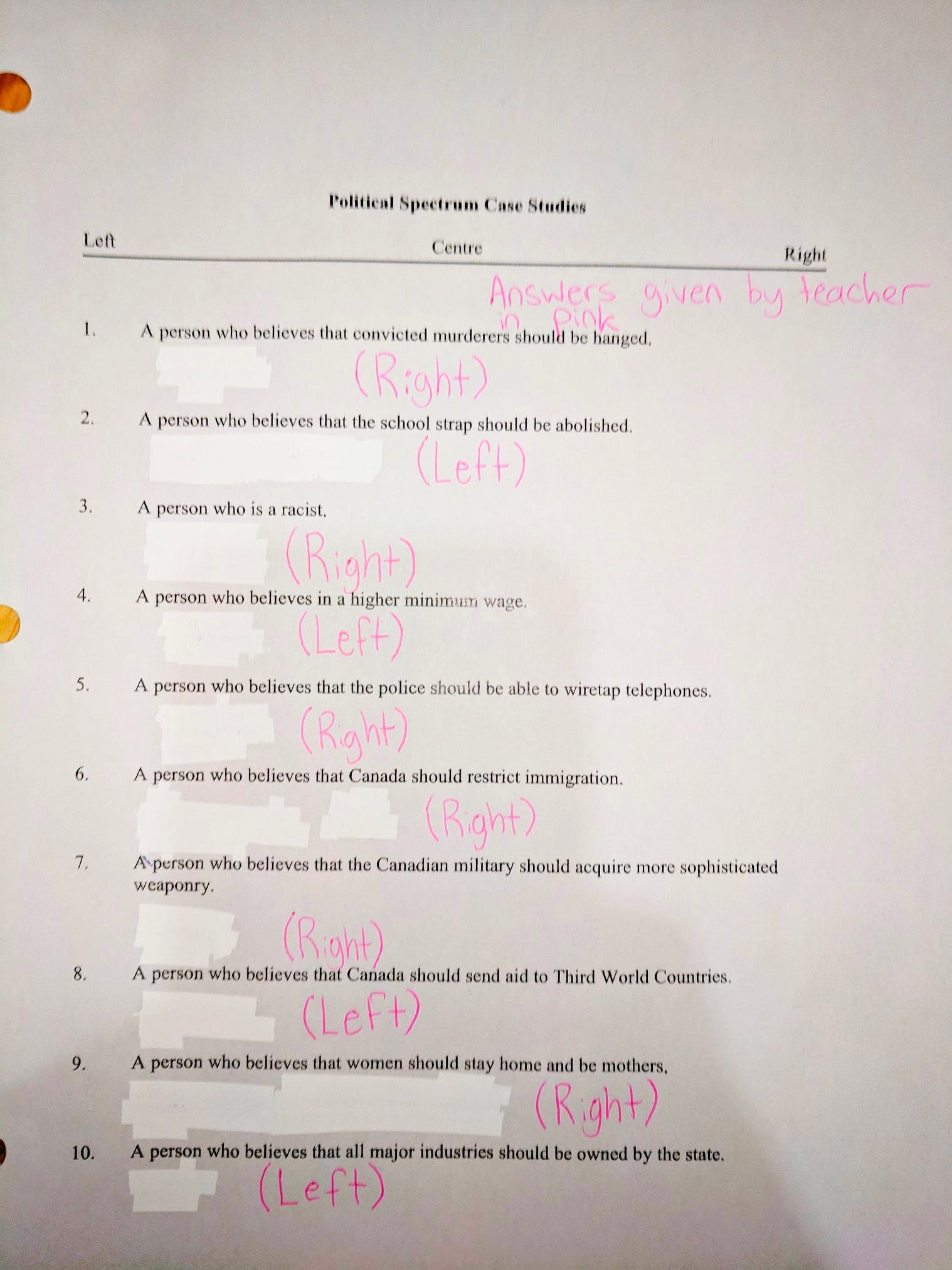

In early October a teacher in Kamloops, British Columbia gave a classroom of grade 10 students a worksheet to help them learn about the ideological spectrum. A few hours later the worksheet – marked up with answers provided by the teacher – went viral on Facebook.

The worksheet asked students to label political positions as right-wing, centrist or left-wing. The teacher’s answer guide indicated that conservatives are racists who support hanging murderers and believe that ‘women should stay home and be mothers.’ According to the teacher, left-wingers believe in abolishing the school strap, raising the minimum wage, and that ‘all major industries should be owned by the state.’

We don’t know the full context of how this worksheet fit into the teacher’s broader approach to teaching political ideology. But, it’s difficult to imagine any circumstance where such a worksheet would have resulted in students leaving the classroom with a nuanced or accurate understanding of the political spectrum.

The story, and the ensuing media dialogue, highlights some important questions that anyone engaged in politics (and politics educators especially) should be asking themselves.

- How do we represent the political views of those we disagree with, especially those of us who are educators?

- What does it actually mean to have a right-wing or left-wing ideology? What does it mean to be a centrist? Are these distinctions sufficient to capture the diversity of political thought?

- What are the roots of conservative and progressive worldviews?

- How does political ideology map onto the partisan landscape in Canada?

- In this politically polarized time, how do we move beyond seeing the world as left versus right, and is it helpful to do so?

In this essay, I explore these questions.

Why teaching the ideological spectrum is hard

Teaching the political spectrum is the most challenging task for anyone who teaches politics. It’s challenging because it requires suspending your own political beliefs in order to accurately represent the beliefs of those you disagree with. Err on the side of not-offending anyone, and you’re likely not advancing your students’ understanding of the material or the realities of present day politics. And, as soon as you offer a clear and crisp definition of anything worth defining, the more likely it is for your own bias to show and influence your students understanding of an important topic.

So let me make my own bias clear off the top. My political beliefs are what most people would call progressive and left-wing. But, I’m also deeply interested in understanding conservative thought. In my experience, the more I understand the perspectives of people I disagree with, the better I am able to articulate my own values.

The less I understand the people I disagree with, the more shallow my defence of my own values becomes. I become mean spirited, engage in petty semantics, and generally assume mine is the only reasonable perspective. Understanding conservative thought, oddly, becomes an opportunity to practice and deepen the progressive values I hold and strive to live up to.

I haven’t met many people on the left who truly care to understand where conservative ideas come from. They’ve seen the branches of conservative thought and don’t want to see the roots. Some see engaging with conservative thought as a waste of time, in the same way they wouldn’t watch a TV show they don’t like. Others fear that discussing conservative thought validates and normalizes conservative positions. The reality is, conservative positions have been normalized for a long time. Engaging with conservative thinking isn’t going to change that. It’s unlikely that conservative ideology will become less prevalent unless progressives truly work to understand the roots of the conservative view.

My own interest in understanding conservative political thought goes beyond “knowing thy enemy.” I’m simply curious. I want to understand conservative thought for the same reason I want to understand what happened on last week’s episode of The Good Place, so that I might better understand what happens on next week’s show.

Ideologies: left, right and centre

There’s another reason why it’s difficult to teach about political ideologies: it’s just plain hard to understand. I’ve made a habit of asking people who belong to political parties what it means to them to subscribe to their particular political ideology. The answers are generally less than satisfying. Most partisans I’ve met are not ideologues, because they don’t know what their ideology is. They can always tell me what policies they support and oppose, but few can articulate an underlying philosophy that might lead one to those policy positions.

Ideology is not partisanship

The words ‘ideological’ and ‘partisan’ are often used interchangeably, and usually in a derogatory way. The words mean different things, and neither word needs to be an insulting term on its own. The dictionary definition of ideology is ‘a system of ideas and ideals, especially one that forms the basis of an economic or political theory, and policy.’ Not all partisans are ideologues, and not all parties have a governing ideology.

Conscious and unconscious, each of us already carries with us an ideology that governs us in life. It may be complex , or it may be simple. It might be front of mind, something that we strive to embody each and every day, or perhaps it’s what we unconsciously use to judge ourselves against when reflecting on those days.

Ideology becomes political when it has to do with people other than ourselves. A political ideology includes assumptions about how the world is and what kind of behaviour is good or bad. Most importantly, a political ideology includes guiding assumptions about if, when and how governments should intervene in the lives of citizens, and how citizens are expected to relate to one another.

Political parties generally exist to allow people who share a political ideology to join forces and work with one another to gain political power and influence. In an ideal world, when a party becomes a part of the government, they shape laws, policies and the political system based on those ideals.

In reality, the closer a party gets to holding elected power, the more their ideology is challenged, and in some cases diluted. The party’s ideals become just one of many factors that influence decision-making in this new reality. Other factors include:

- the slow pace of bureaucracy,

- long term agreements with service providers, unionized workers, and other governments,

- the watchful eye of the media,

- economic events and natural disasters,

- previously hidden circumstances,

- voters and public opinion,

- opposition parties, and

- any division or debate happening within a political party as a result of these new circumstances.

In all cases, the party must decide how it will negotiate its ideals with the realities of seeking and holding power.

Robert J. Hanlon once wrote, “Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.” In politics, it’s worth adapting Hanlon’s razor to warn those who might too quickly draw conclusions about an ideology based on how a party with that ideology performs once in power:

Never attribute to ideology that which is adequately explained by the inexperience and overwhelmedness of the political party espousing that ideology.

An ideology explains how your various beliefs are connected

A political platform is not an ideology. A purity checklist is not an ideology. An ideology is more than a list of beliefs about how things should be. An ideology should help you understand how all of your separate beliefs connect to one another. An ideology is resilient if it can guide your decision-making in new and unexpected circumstances.

Let’s explore some examples of beliefs that commonly (but don’t always) live together in politics. If you identify as a left-wing progressive in Canada, you might find yourself agreeing with the following three statements:

- Averting climate change is more important than getting oil to market.

- Wealthy corporations and individuals should pay higher taxes than they do right now, since their wealth was (in part) made possible by many publicly subsidized services and publicly funded infrastructure.

- The criminal justice system is unfair, punishes many people whose options were limited by social circumstance too early in life, and doesn’t do enough to set them up to succeed when they leave prison.

If you identify as a right-wing conservative in Canada, you might find yourself agreeing with the following three statements:

- Getting Canadian oil to new markets should be more important than averting climate change.

- Those who earn more should be rewarded for their successes, not punished with higher tax rates.

- The justice system is meant to punish those who choose to commit crimes. Any reforms to that system should keep that purpose at its centre, and we should be cautious of new programs with alternative goals.

Understanding a political ideology is about more than just understanding which positions are supported or opposed by that ideology. To truly understand a political ideology means knowing how the positions supported by that ideology relate to one another. It’s also about understanding how people who identify with the same ideology might reach different answers to the same question.

(You may identify as a progressive or conservative and not agree with one or more of the policy positions noted above on the respective lists. If that describes you, I’d invite you to keep reading, and then let me know why you feel that way in the comments, after you’ve read the remainder of the article).

Political ideology is often rooted in subconscious metaphor

I suspect most people don’t fully understand the roots of their own political and moral worldviews, let alone the views of those who disagree with them. I didn’t understand mine before I read George Lakoff’s work (h/t FrameLab). Lakoff is a cognitive linguist who studies politics in the United States. He is a progressive Democrat, and his framing of progressive policy is brilliant. His ability to do that, however, came from his efforts to understand conservative thought and communication, which included immersing himself in the world of conservative talk radio.

Lakoff suggests that conservatives and progressives understand governments best through an unconscious metaphor of the family. In this metaphor, nations are people, and leading a government is like leading a family. In Lakoff’s world of metaphor (which he argues, is one we all already share), conservatives adopt a moral worldview where the ideal style of leadership is that of a ‘strict father’. Progressives adopt a moral worldview where the ideal leadership style is that of a nurturant and forgiving parent.

Conservative ideology and the strict father

An ideology includes (often implicitly) a set of assumptions about how the world is. In the world of ‘strict father’ conservatism, the assumptions about the world are harsh. Lakoff writes:

The world is a dangerous place, and it always will be, because there is evil out there in the world. The world is also difficult because it is competitive. There will always be winners and losers. There is an absolute right and an absolute wrong. Children are born bad, in the sense that they just want to do what feels good, not what is right. Therefore they have to be made good. What is needed in this kind of a world is a strong, strict father who can:

– Protect the family in the dangerous world,

– Support the family in the difficult world, and

– Teach his children right from wrong.

Lakoff isn’t introducing a new idea, he’s articulating a longstanding narrative and approach to parenting. The ‘strict father’ can be found in parents of either gender, in classroom teachers, employers and sports coaches. Strict father figures are present throughout the stories that children of many cultures grow up hearing and viewing about morality and family life.

The strict father has several expectations of the children raised in his household:

What is required of the child is obedience, because the strict father is a moral authority who knows right from wrong. It is further assumed that the only way to teach kids obedience — that is, right from wrong — is through punishment, painful punishment, when they do wrong.

[When children are disciplined], they learn not to do it again. That means that they will develop internal discipline to keep themselves from doing wrong, so that in the future they will be obedient and act morally. Without such punishment, the world will go to hell. There will be no morality.

Such internal discipline has a secondary effect. It is what is required for success in the difficult, competitive world. If people are disciplined and pursue their self-interest in this land of opportunity, they will become prosperous and self-reliant. Thus, the strict father model links morality with prosperity. The same discipline you need to be moral is what allows you to prosper. The link is individual responsibility and the pursuit of self-interest. Given opportunity, individual responsibility, and discipline, pursuing your self interest should enable you to prosper.

Morality, in the eyes of Lakoff’s strict father, is the product of self-discipline and the pursuit of self-interest. The one who must adhere to these standards is the child (citizen), because the father (government) is presumed to already be the moral authority.

A good person — a moral person — is someone who is disciplined enough to be obedient to legitimate authority, to learn what is right, to do what is right and not do what is wrong, and to pursue her self-interest to prosper and become self-reliant. A good child grows up to be like that. A bad child is one who does not learn discipline, does not function morally, does not do what is right, and therefore is not disciplined enough to become prosperous. She cannot take care of herself and thus becomes dependent.

…

It is moral to pursue your self-interest, and there is a name for those people who do not do it. The name is do-gooder. A do-gooder is someone who is trying to help someone else rather than herself and is getting in the way of those who are pursuing their self-interest. Do-gooders screw up the system.

In today’s political discourse, we might replace the term do-gooder with ‘social justice warrior.’ As far as the strict father is concerned, do-gooders and social justice warriors not only screw up the system, but threaten the legitimacy of the father’s moral authority.

The strict father worldview is so named because according to its own beliefs, the father is head of the family.

Any truly conservative program is built on strict father values. Conservatives (generally) want smaller government with less red tape to ensure that those who have practised self-discipline are rewarded for their efforts, not punished by government regulation. Good governments, like good fathers, don’t intervene in the lives of citizens in ways that might reward a lack of discipline. Doing so could create dependency, which is immoral. However, since ideological conservatives believe that government should be a moral authority that shares their values, intervention to exert that moral authority is sometimes necessary.

Progressive values are nurturant parent values

Lakoff offers the model of a ‘nurturant parent’ to represent progressive values.

The nurturant parent worldview is gender neutral. Both parents are equally responsible for raising the children. The assumption is that children are born good and can be made better. The world can be made a better place, and our job is to work on that. The parent’s job is to nurture their children and to raise their children to be nurturers of others.

What does nurturance mean? It means three things: empathy, responsibility for yourself and others, and a commitment to do your best not just for yourself, but for your family, your community, your country and the world.

If you have a child you have to know what every cry means. You have to know when the child is hungry, when she needs a diaper change, when she is having nightmares. And you have a responsibility — you have to take care of the child. Since you cannot take care of someone else if you are not taking care of yourself, you have to take care of yourself enough to be able to take care of the child.

All this is not easy. Anyone who has ever raised a child knows that it is hard. You have to be very strong. You have to work at it. You have to be very competent. You have to know a lot.

Like the strict father archetype, Lakoff isn’t describing anything new here. Nurturant parents are present in all cultures. Their reactions are distinctly different than those of the strict father. The strict father’s priority is raising a child who is disciplined to succeed in any environment. The nurturant parent is interested in setting the child up for success in the environments they control, and by protecting them from those things that may cause them harm.

In addition, all sorts of other values immediately flow from empathy, responsibility for yourself and others, and commitment to do your best for all. Think about it.

First, if you empathize with your child, you will provide protection. This comes into politics in many ways. What do you protect your child from? Crime and drugs, certainly. You also protect your child from cars without seat belts, from smoking, from poisonous additives in food.

….

Second, if you empathize with your child, you want your child to be fulfilled in life, to be a happy person. And if you are an unhappy, unfulfilled person yourself, you are not going to want other people to be happier than you are. The Dalai Lama teaches us that. Therefore it is your moral responsibility to be a happy, fulfilled person. Your moral responsibility! Further, it is your moral responsibility to teach your child to be a happy, fulfilled person who wants others to be happy and fulfilled.

Lakoff goes on to detail how values like freedom, opportunity, fairness, transparency, and cooperation flow from the nurturant parent mindset.

Every progressive political program is based on one or more of these values. That is what it means to be a progressive.

The nurturant parent mindset is inherently more complex than the strict father. The nurturant parent is concerned about the systemic factors that could affect their children’s success in life, and continues to take this context into consideration when the child has failed to live up to their hopes and expectations.

A nurturant parent progressive wants to give citizens second chances. Progressives emphasize reimagining the social order, the economic system, the justice system, and political systems in order to ‘level the playing field.’ Conservatives are more interested in ‘reforming’ these systems to reward and punish individuals according to their behavior. The conservative strict-father sees progressives as ‘do-gooders’ who are ‘screwing up the system’, while the progressive, nurturant parent sees the system as already ‘screwed up’ and tries to improve it.

Because they generally want smaller government, conservatives can easily find agreement on the kind of programs governments should stop offering. Because they are focused on the people and issues slipping through the cracks of the current system, progressives are never short of reasons to argue with one another about which new programs should take priority.

Strict fathers and nurturant parents are already in our brains

Lakoff suggests that the strict father and nurturant parent archetypes are represented by neural circuitry in our brains called ‘frames.’

Frames are mental structures that shape the way we see the world. As a result, they shape the goal we seek, the plans we make, the way we act and what counts as a good or bad outcome of our actions. In politics our frames shape our social policies and the institutions we form to carry out policies.

You can’t see or hear frames. They are part of what we cognitive scientists call the “cognitive unconscious” — structures in our brains that we cannot consciously access, but know by their consequences. What we call “common sense” is made up of unconscious, automatic, effortless inferences that follow from our unconscious frames.”

There is no such thing as a centrist ideology

Lakoff’s work is based on American politics, and targeted towards an American audience. In the two-party system of the United States, it is easy to see how the ideology of Republican and Democrat, line up nearly perfectly with the values he articulates for the strict father conservative, nurturant parent progressive. In Canada’s multi-party system, and everywhere else multi-party politics is the norm, the strict father and nurturant parent frames are still active, but don’t sit neatly within one party or the other.

Moderates, or centrists, don’t have an ideology, as far as Lakoff is concerned.

… a great many people operate on different — and inconsistent — moral systems in different areas of their lives. The technical term is “biconceptualism.” … I have colleagues who are nurturant parents at home and liberals in their politics, but strict fathers in their classroom.

…

Here the brain matters even more. Each moral system is, in the brain, a system of neural circuitry. How can inconsistent systems function smoothly in the same brain? The answer is twofold:

(1) mutual inhibition (when one system is turned on, the other is turned off); and

(2) neural binding to different issues (when each system operates on different concerns).

…

Biconceptuals have both kinds of moral circuitry in their brain, mutually inhibiting each other and applying to different issues, person by person. There is no “middle,” no morally based political ideology common to all moderates.

Centrists, in other words, are those who sometimes agree with the approach of the conservative, strict father, and other times agree with the approach of the progressive, nurturant parent.

“I’m not a left-wing thinker, or a right-wing thinker, I’m a forward thinker,” is a response often heard from municipal politicians, community leaders and others. But, Lakoff’s analysis suggests that there is no such thing as forward thinking centrists — there isn’t a moral frame behind that label. A more fitting response for those who sit in the supposed ‘middle’, might be, “Sometimes I think the conservatives are right, sometimes I think the progressives are right, sometimes nobody is making any sense.”

Lakoff casually estimates that “35 to 40 percent of people have a strict father model governing their politics,” and suggests a similar amount have a nurturant parent model governing their politics. The rest are bi-conceptuals, who are under the joint custody of strict father and nurturant parent worldviews.

The political spectrum in Canada and other multi-party states

It’s impossible to neatly apply Lakoff’s framing to the parties on the political spectrum in Canada. While Canadian Liberal and Conservative parties draw support from the left and right respectively, each party keeps an open door for card-carrying bi-conceptuals.

Many provincial conservative parties in Canada hold onto their ‘Progressive Conservative’ branding. In addition to their conservative programs, PC parties have introduced legislation and policy that could have just as easily been passed as flagship policies by Liberal or NDP governments. Former NDP premier of Nova Scotia, Darrel Dexter, once jokingly described himself as a ‘conservative progressive.’ And then there are the Greens, who will surely face a nurturant parent vs. strict father identity crisis should they ever gain power.

Does this mean Lakoff’s framing of the strict father and nurturant parent archetypes aren’t useful in understand the politics of multi-party nations like Canada? Hardly. The two world views are already prevalent in our culture, our parenting, and our politics too. Those world views just don’t track as tidily along partisan lines. Both parents show up in the policy positions adopted by both conservative and progressive movements, as well as the leadership styles of party and movement leaders across the political spectrum.

A sheep in wolf’s clothing?

It is Lakoff’s nurturant parent that expects a stronger public health care system. It’s the nurturant parent who wants criminal justice reform. It’s the nurturant parent who is unthreatened by the marriage of same-sex couples, and who supports legislation that would allow them to do so.

The nurturant parent also seems to show up in some approaches that are popularly considered ‘conservative.’ It’s the nurturant parent who acknowledges that individual behaviour change is slow, and that culture change is even slower. It’s the nurturant parent that understands that shaming and blaming someone for their minor transgressions isn’t a sustainable way to improve society. And, it’s the nurturant parent who extends second chances to the powerful and wealthy, not just the powerless.

The strict father’s actions are motivated by a belief in his own rightness and an equal belief in his entitlement to act accordingly when that rightness is threatened or violated. It’s the strict father who demands tougher sentences for criminals convicted of small crimes. It is the strict father who wants to lower the tax burden on businesses and citizens with high levels of income. It’s the strict father who would rather see health care dollars go towards cancer treatment than covering the cost of abortions.

Similarly, progressive movements and parties aren’t completely above taking a strict father approach to leadership. It’s the strict father who rewards party loyalty, and solidarity. It is the strict father who wants to penalize those who don’t sort their waste into recycling and compost. And it’s the strict father who is unforgiving to those who don’t tick every box on the progressive, purity checklist.

Once governments are elected espousing progressive nurturant parent policies, or conservative strict father policies, there is room for each to employ the leadership style of the other in advancing those policies. Left-wing authoritarians like Fidel Castro introduced nurturant parent social policies by exercising the control of a strict father. Right-wing libertarians don’t advocate strict-father style of politics over the states they seek to govern, despite seeking policies that would have a strict-father effect.

These examples illustrate that the political spectrum is not a one-dimensional spectrum, but at least a two dimensional one. One dimension describes the kind of legislation, programs and regulations that society will be ordered by in the ideal future espoused by that ideology. The other dimension describes the lengths to which those who hold that ideology are willing to go in order to achieve and maintain that ideal future.

Searching for a worldview that transcends the right and left divide

I’ve taught Lakoff’s work in classes on political communication that I’ve run for activists and other public leaders. The ideas he presents prompt people to think about what a more complete, more holistic view of the political spectrum might look like. Participants raise questions about how a nurturant parent should engage with the strict fathers who they will inevitably encounter in public life.

Lakoff’s work isn’t intended to give a satisfying ‘theory of everything’ on political ideology. He’s trying to help Democrats win elections. His work isn’t so much inaccurate as it is incomplete. The strength of Lakoff’s work is that it is both theoretical and practical. His illustration of the nurturant parent progressive and strict father conservative lays the foundation for an effective approach to political communication. But that’s more or less where his guidance ends.

In a world as politically polarized as ours, I’m not interested in an ideology that oversimplifies, or is silent on how to address the growing political polarization in society. A truly progressive ideology should also offer guidance on how those who hold it ought to relate to people of differing political ideologies, and those who take differing political positions on issues — including those that offend us.

When I look at modern political movements, especially those in Canada, I see little guidance for how to relate with those of differing political beliefs. There are some leaders within those movements who have modelled a kind of political behavior that instills hope. But, those leaders are few and far between, and it appears to me that their moral inspiration comes from a place inside themselves that is bigger than the political ideology they share with their movements.

Political ideologies are something like personalities. Our personalities (I am told by my elders) tend to stay somewhat consistent as we grow and learn. We learn to engage with difference, and negotiate living in the world with other people, while the thing that makes us unique stays the same. This kind of maturation is a given for most individuals, but it’s a rarity for group development.

In politics, it’s time for our ideologies to grow up and learn to relate to one another in a sustainable constructive way.

— –

I’m currently writing about ‘growing up’ our ideologies for a future essay. When it’s ready, I’ll link to it [here].

Thank you for reading. These posts are where I share my own learnings in my work as a politics educator. For me, writing is first and foremost an exercise in self-education. I write when I’m confused. When I’m finished writing, I’m less confused. What ends up posted here will, at best, be an incomplete answer to questions I continue to explore. If this article has sparked something for you that might be of interest to me and other readers, share that spark in the comments.