On Monday morning, Justice Edward P. Belobaba of the Ontario Superior Court released his decision to strike down the controversial legislation introduced by the Ontario government that would have reduced the size of Toronto City Council mid-election.

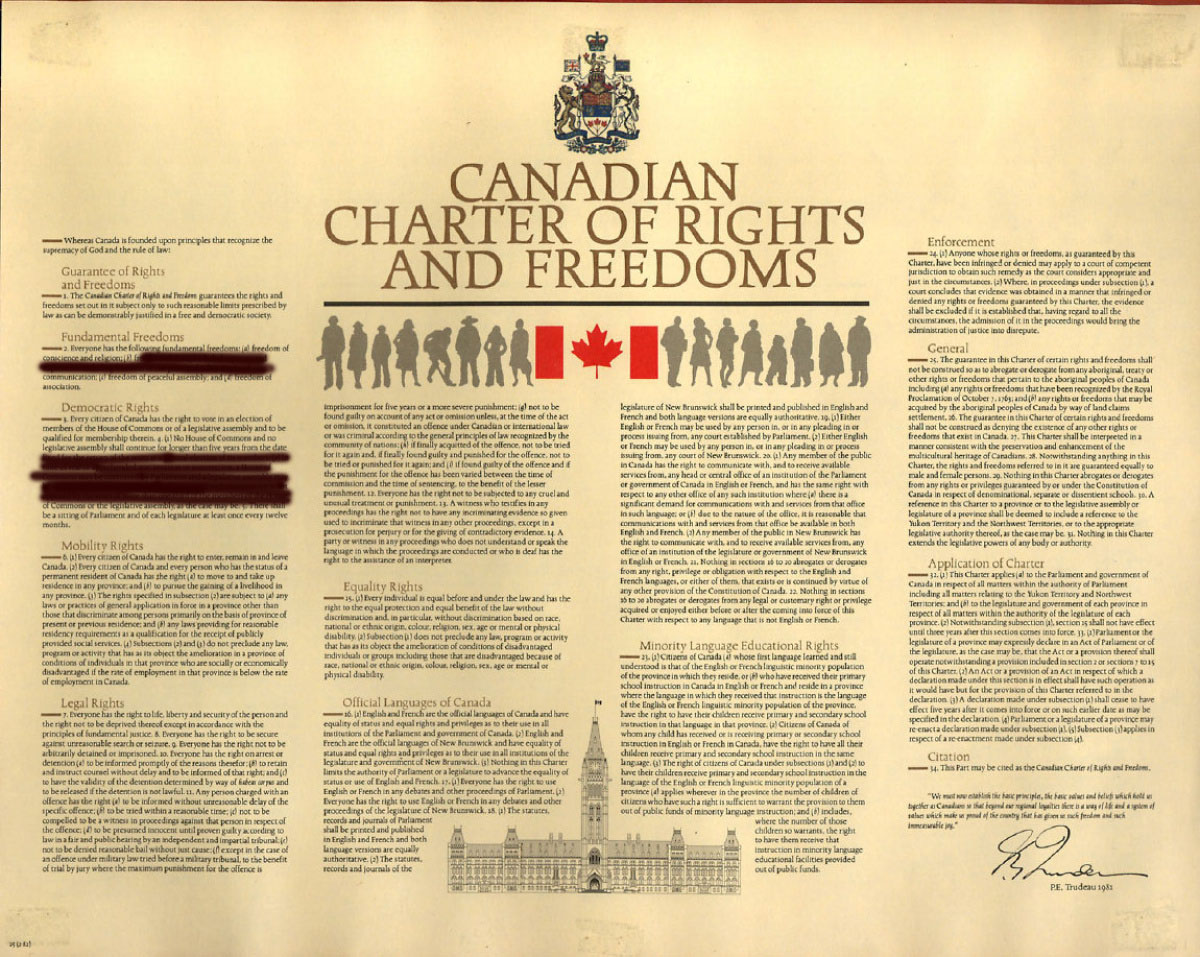

Ontario Premier Doug Ford promptly responded by indicating that his governent would be appealing the decision and introduce legislation that would invoked the Charter’s notwithstanding clause. Doing so will ‘immunize Bill 5 from judicial scrutiny’. The clause allows a provincial legislature, or parliament to override court ruling’s like the one issued monday when those rulings rely on certain parts of the Charter.

Why do we even have a notwithstanding clause?

Sean Fine, justice writer for the Globe and Mail, has written a thoughtful explainer of the notwithstanding clause. In it he addresses a likely starting point for many readers, and perhaps a helpful refresher for others: why do we even have a notwithstanding clause?

Three Western premiers proposed the clause at a First Ministers Conference in 1981 so legislators could have the last word. “We needed to have the supremacy of the legislature over the courts,” Alberta Premier Peter Lougheed said, citing the experience of the United States, in which courts had struck down legislation limiting work hours and the use of child workers. Mr. Lougheed was one of two Progressive Conservative premiers (the other was Sterling Lyon of Manitoba) who joined with a New Democrat (Allan Blakeney of Saskatchewan) to propose the clause. So it was a compromise between political power and judicial power – a kind of “safety valve,” as the justice minister of the day, Jean Chrétien, viewed it.

Fine explains that, outside of Quebec, the clause is rarely used. While the Court could conceivably be asked to rule that Ford’s invocation of the notwithstanding clause is beyond those limits, it’s unlikely they would do so.

From the CBC:

Politically, the notwithstanding clause is a particularly powerful tool, said Eric Adams, constitutional law professor at the University of Alberta. “Efforts to challenge the reasoning behind the use of the notwithstanding clause have not succeeded to date,” he said, referencing more than a dozen past incidents. In other words, when a provincial government invokes the clause, they almost virtually always get their way.

How the notwithstanding clause should be used: two theories

University of Ottawa Law Professor, Vanessa MacDonell unpacked the theory on the use of the notwithstanding clause on Twitter.

Regarding Ford’s announced plan to use the notwithstanding clause… There are two theories of the use of the notwithstanding clause.

The first is that the clause is invoked when the government proposes legislation that (very) likely infringes constitutional rights.

The second is that the clause is legitimately invoked when the government believes its proposed legislation is constitutional on a different interpretation of constitutional rights than the one a court has provided.

This second theory is the interpretation of the clause I prefer, though it’s the less popular one.

I haven’t seen Ford say that they are invoking the clause based on this second theory, though the fact that they are also appealing the decision could lend credence to this kind of argument.

Invoking the notwithstanding clause is not a normal reaction to an adverse court ruling, particularly if you think the law is on your side and you are dealing with a trial-level ruling.

My sense is that the timing of the election is driving this.

My preliminary view is that we should be very concerned about Ford’s statement that he’s not afraid to use the notwithstanding clause and will use it again if necessary.

Whatever you think of the notwithstanding clause, few would advocate for government-by-notwithstanding-clause.

I don’t know whether, as some suggest, this is personal for Ford. But what I do know is that there should be serious, reasoned deliberation within the executive before legislation is proposed that invokes the notwithstanding clause.

As of yet I haven’t seen the government argue that it is invoking the notwithstanding clause because it believes the legislation is constitutional or explain the principles which justify overriding constitutional rights here. We need to see such a justification.

The Court found in this morning’s decision that the reasons for the infringement of constitutional rights were “improved efficiency and overall cost savings.” In fact, the Court found that the law did not further a “pressing and substantial objective.”

This is a pretty remarkable finding.There should also be deliberation in the legislature. I hope opposition MPs press the government for a rationale.

Andrew Coyne writes:

[The notwithstanding clause] is to be sure, part of the charter, as much as the rights whose override it permits For its message is essentially to negate the rest.

…

The rights so gaudily guaranteed in the charter, it says, are not in fact guaranteed at all. They are not permanent and universal, but temporary and contingent — not even rights, really, so much as permissions. And what the government gives it can take away.

Certainly there is nothing remotely “conservative” about it. Whatever else conservatism may be about, it is supposed to be about limited government — government that, large or small, is required to behave according to certain rules, in a predictable, non-arbitrary way. As opposed, say, to populist strongmen making it up as they go along.

‘Like using a drone strike to deal with a boisterous block party’

Carissima Mathen, also a law professor at the University of Ottawa, writes in the Globe and Mail:

Ontario’s plan to invoke the notwithstanding clause – inserted into the Charter as part of final negotiations, and rarely used – was bound to be controversial. One might expect Section 33 to be used to respond to, or prevent, court decisions that imperil public safety (say, that strike down serious criminal offences) or wreak havoc to government’s finances. To use Section 33 then to maintain a preferred size of a city council is completely out of proportion – like using a drone strike to deal with a boisterous block party.

The Ontario government had at least an arguable basis on which to explain the decision: By invoking Section 33, it could have presented itself as maintaining certainty and the status quo for the municipal election while also seeking to appeal the lower court ruling.

The problem is with how the Premier described his decision. He said the use of the notwithstanding clause was justified because of his political mandate. He said he was elected – and Justice Belobaba was merely appointed.

A dangerous precedent?

The notwithstanding clause is available to any premier that wishes to use it. It has been since the Charter and constitution were introduced nearly forty years ago. It’s one of the release valves available to premiers, thanks to the political climate surrounding the negoations that brought us the Canadian Constitution.

Canadian provincial and federal governments have historically shown a great deal of restraint around the notwithstanding clause, rarely overruling a court’s decision. Past governments’ reluctance to invoke the notwithstanding clause is now contrasted against the Ontario government’s enthusiasm to do so. One might wonder how other present-day premiers will react to Ford’s approach. With judgement? Or jealousy?

Paul Wells writes in MacLean’s:

[C]ongratulations, Ontario Conservatives. The notwithstanding clause just showed up, after long absence, in the toolkit of any Quebec government that might grow impatient with minority-language rights. Or any government anywhere that finds free speech, free association, peaceful assembly or religious freedom to be silly obstacles on the way to settling whatever personal scores animate them.